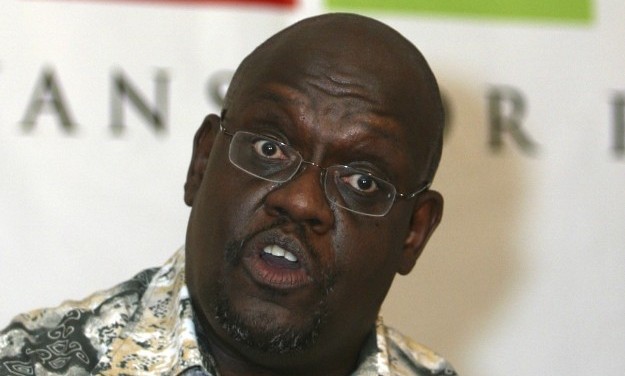

In February 2005, John Githongo fled his native Kenya fearing that his life was in danger: as the country’s Permanent Secretary for Ethics and Governance he had uncovered an alleged corruption scandal (the Anglo Leasing affair) which seemed to penetrate the heart of the government in Nairobi. A well-known advocate against corruption he ran the Kenyan branch of Transparency International before joining the government in 2002 – the publication, in 2006, of his 36page dossier on Anglo Leasing put him into the international news headlines. He finally returned home in 2008 and since then has set up Inuka Trust, a grassroots movement which encourages Kenyans to be responsible for improving their own lives.

Global: The August 2010 referendum on constitutional reform passed off peacefully and there seems to be a sense of optimism that the amendments, if enacted by Parliament, will address the issues of corruption, political patronage, land grabbing and tribalism that have plagued Kenya since independence in 1963. What are your thoughts on the new Constitution and the impact that it will have on governance?

John Githongo: The new Constitution creates for Kenya a moment of hope, which is very important because [the events of] 2007/8 took that away from us. It took us to a very dark place where violence had brought us to grief, but the Constitution now helps us once again. You have to be in a hopeful positive space to be able implement the measures that will eventually deal with the fundamental problems society faces. So in that sense the Constitution is a good thing. It’s going to take heavy lifting to implement it, especially those provisions to do with land, devolution and the fact that we now have a much more robust legislature. But I think these are good problems to have in that they are forward-looking as opposed to being prisoners of the past.

Are you hopeful that Kenya can solve its problems?

I cannot afford to be pessimistic. I am realistic. The prospects that are promised by pessimism are horrifying. If you think of Kenya’s contradictions we are one of the most unequal societies in the world, we have a population growing at about one million per year, only 13 percent of land is arable and 80 percent of the population is crammed into it. We have some of Africa’s most rapidly growing cities, we are completely ethnically polarised and we have a venal, tiny elite. If you think of everything against us and put it all together then you can die of depression. So you’ve got to flip it. Kenyans turned out in huge numbers to vote for the new Constitution, they registered in great numbers to vote for it, so people remain committed to democratic processes and that’s very special. I think Kenya has a chance to become and remain a leading African country.

Following the disputed election in December 2007, with the subsequent killings and displacement of people from their homes, do you think Kenyan politics will ever be free from tribal rivalries? What, in your opinion, needs to happen to ensure that ethnic loyalty is removed as a factor from the political system?

I think that when you have over 1,000 people dead and, at one point, over 600,000 people displaced, things will never be the same again. It has changed for good. The myth of Kenyan exceptionalism died with that. We used to think Kenya was a special place but that has changed. We in the middle class would like to think it is still there. The damage that is done as a result of the violence along ethnic lines – when blood has been spilt – takes generations to heal and we are just starting.

Is there anything that can help speed up the process?

The most important thing is leadership that recognises that this is a crisis that needs to be dealt with very proactively. There are provisions within the new Constitution, which if implemented in the spirit – not only the letter – would go some way. But one has to recognise that it will take time. It means making special provisions for historically marginalised groups – groups that have been marginalised along ethnic lines, along regional lines – dealing with that in a proactive manner so that we can create a properly inclusive society. You can have all the good laws and constitutions and nice pieces of paper but unless you have leadership that exemplifies that kind of inclusive culture then you will have difficulties.

As a former editorialist, are you confident that the Kenyan media in all its various manifestations – radio, TV, the printed press and new media – are set on a promising path, playing a responsible role in nation-building and encouraging more open and productive debate among citizens?

I think the Kenyan media has always been amongst the most sophisticated in the region and I think they have played a positive role in helping to foster reconciliation, during and after the post-election violence. However, we’ve seen a lot of fragmentation in the media – we have countless little local radio stations and the quality varies. At the national level we’ve seen a consolidation and a concentration in terms of political and commercial ownership of the national media and that alignment sometimes is not always healthy. But it is something that we are aware of and can mitigate.

Is religion playing more of a positive or a divisive role in Kenya’s political evolution?

It’s never been that much of an issue in Kenya’s politics. It became an issue in the referendum because of the Kadhi Courts and the churches took a stand against the Constitution. However people still went ahead and voted overwhelmingly for the Constitution and Kenyans are a very religious population so one can see this as a secularisation – that Kenyans were saying that we are very religious people in our private space but in our public political space we would like religion not to be so much of a player. I still think that the religious leadership has a potentially important role to play in reconciliation, especially when we talk about the ethnic violence of 2007/8. They have the equipment of healing and forgiveness and redemption that is not available to any state. So they remain important actors in long-term reconciliation. However, they are in the middle of a leadership crisis too.

Kenya is, demographically speaking, a very young country – around 75 percent of the population is under the age of 34. Are the youth engaged in politics?

Very! It’s the youth who came out to vote for the Constitution. We have had a number of by-elections in the past year and there have been surprises which have been youth driven. The violence in 2007/8 was driven by the youth. The violence itself was the single most empowering event for young Kenyans since independence because they discovered that you can take a machete and block trade with Uganda – very anti-social, but they realised they could do it and they shocked the state. The international community also panicked. The youth are at the heart of it. We have a youth bulge that should be Kenya’s engine to becoming an African leader but right now it’s treated as a crisis. I think we can flip it because they remain committed to democracy. All they seek is new, better leadership and a better framework of the kind that is partly promised by the imperfect Constitution which has just been passed.

What is your opinion of the recent moves in which a senior minister, the Mayor of Nairobi and other senior officials have been forced to resign while investigations are conducted into alleged corruption? Do these developments promise to build positively on the groundwork that you initiated while you had responsibility for investigating corruption seven years ago?

These are all exciting developments that follow the recent passage of the new Constitution. I’m cautious, however, as we have previously witnessed a multiplicity of anticorruption spasms orchestrated by the inner core of the ruling elite mainly to extract resources from the international community. It remains to be seen whether this is such an episode.

In setting up Inuka Trust you’ve been working at the grassroots level to eliminate corruption. Why do you believe that this kind of approach will be more successful than attempts to tackle the problem through state-financed anti-corruption agencies?

I think both work together. However when I joined the government the most successful time we had in the fight against corruption was a period of about six to eight months in 2003 when we had ordinary Kenyans arresting policemen and other public servants for taking bribes. That was our most successful time. We almost didn’t know what to do with it. It’s a success when ordinary people believe that they can shake off the shackles of corruption because at that level, for the poor, corruption is extortion. Imagine a woman taking her child to a hospital and she is being asked to pay a bribe before an x-ray is taken. Is she corrupt? What choice is she being forced to make at that point? When you have ordinary people taking matters into their own hands in that way and creating a groundswell against corruption then you are succeeding in the fight. And that also creates the pressure to force leaders to change because leaders are sensitive to that, in a democratic context.

What, if anything, can international donors and financial institutions do to encourage better governance in Kenya and other African countries?

I think first of all Kenya doesn’t need aid. Kenya collects around $4.2 billion in taxes each year so we don’t actually need aid. What can the international community do? The first rule of engagement should be do no harm. Before doing anything, make sure you know what you are doing. There is no template. One size doesn’t fit all in countries where you are trying to promote development. Secondly, ensure that there is alignment between the foreign policy, the security policy and the development policy. When you are talking about aid sometimes there are mismatches, conflicting signals that can lend succour to elites that are sometimes bent on doing the very wrong thing with regard to the rights of their population.