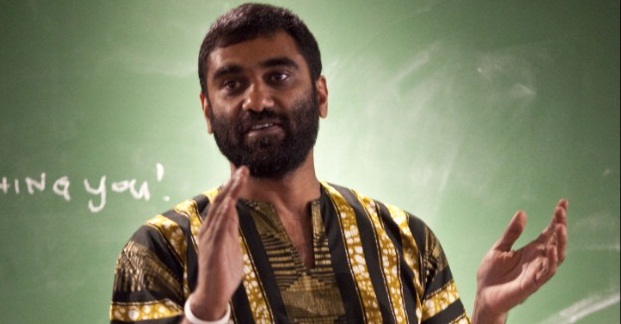

In June last year, Kumi Naidoo spent four days in a prison in Greenland for scaling an Arctic oil rig – braving the freezing jets of powerful water cannons – in breach of a court injunction forbidding Greenpeace to go within 500 metres of the semisubmersible rig. This was not the first – and surely won’t be the last – act of defiance by a man who has devoted most of his life to fighting injustice and oppression. Growing up in Durban, South Africa, he spent his youth challenging the apartheid regime. This was where he honed his radicalism and learnt firsthand the value of civil disobedience.

Before joining Greenpeace in 2009, Naidoo headed Civicus, a Johannesburg-based organisation dedicated to strengthening citizen action and civil society across the world. He was also co-chair of the Global Call to Action Against Poverty. He has been criticised by some in the green movement for not being an environmentalist but, as Naidoo explains in this exclusive interview with Global, the struggle against poverty and the fight to defend the Earth from exploitation are one and the same.

Global: Almost 20 years to the day since the first Rio Earth Summit, the UN is convening a conference on sustainable development – Rio+20. Can you identify any progress that has been made during the past two decades?

Kumi Naidoo: In 1992, we contributed to ending the false dichotomy between environment and development. Governments pledged to make development work for all, including for future generations.

In many ways, this was quite a significant breakthrough and remains our real global challenge – to deliver decent lives for all within the ecological boundaries the planet sets for us. Since Rio, key environmental agreements such as the Kyoto Protocol have been agreed.The summit 20 years ago set in motion things that would ensure that [in 2011] investments in renewable energies have overtaken investments in fossil fuel technologies for the very first time.

What are Greenpeace’s hopes and expectations for the outcome of the meetings in June?

At Rio our main demands are that governments begin to listen to people and put their interests first – not the polluters’. It’s a very small but powerful group of players that are holding us back. If you take a company like Asia Pulp & Paper, [it] is one key reason why Indonesia does not have proper forest protection. Volkswagen [too] has fought aggressively against climate protection rules we need in Europe and the US. The finance industry has succeeded also in making the taxpayer pay for its bad decisions and it’s stopping governments from effectively regulating global financial markets.

So if Rio+20 is to deliver to the world and be credible, [it] must support an energy revolution based on renewable energy and, at the same time, have a plan to provide energy access to all – 1.6 billion people in the world today do not have access even to a single light bulb. We are [also] pushing for a commitment to zero deforestation by 2020.

A specific thing we hope will come out of Rio is that governments agree to upgrade the United Nations Environment Programme to specialised agency. If you look at the failure of climate negotiations, you can’t blame the UN for it – it’s the positions that governments take. But I do think the UN [should] look at how they can be much more efficient and effective.

Another key test for Rio is that governments finally must launch negotiations to protect the high seas, which have been plundered ‘Wild West’-style. Our oceans are under threat and Greenpeace is calling for a new implementing agreement under the existing UN Convention on the Law of the Seas that ensures the conservation of marine biodiversity as well as sustainable management of human activities.

Obviously we hope the outcomes will be ambitious [and] reflect that the climate crisis is not something we will hit in the future. It’s with us now. It’s taking lives to the tune of 300,000 a year. We are seeing records in temperatures, violent swings in temperatures. Already that is impacting on agriculture. Time is fast running out.

One of the themes of Rio+20 is the green economy. What would a fair and just green economy look like and how could it be achieved?

Firstly, a fair green economy is always presented as some utopia. We would argue that it is completely achievable, but it requires political will and urgent action. Right now we need to be looking at how we can be promoting sustainable practices, but above all, governments must put a decisive end to unsustainable practices. An economy based on nuclear energy, oil and coal, genetic engineering, toxic chemicals [and the] over-exploitation of our forests and seas will never be green.

The fair green economy that we want is one that provides sustainable livelihoods for all, while fully respecting ecological limits. In a truly green economy we would expect that the economy will be a mechanism to deliver societal goals, and that economic growth, as an end goal in and of itself, will be abandoned. Because right now the drive for profit is putting the people and the planet below the rapacious need for a handful to make humongous profits.

The good news is the transformation we are calling for is taking place – too slowly, OK – but there are signs. For example, in Germany in the last decade, 81 percent of installed power capacity was renewable. And Greenpeace has developed the ‘energy revolution scenario’, together with a range of other think tanks. [It] has two tracks: investing seriously in energy efficiency and investing seriously in renewable energy. We have done studies, country by country, which show that, with this twin-track approach and with real commitment by the political leadership, we can generate additional jobs and reduce emissions by 80 percent by 2050. So we get a double win – it’s good for the environment but also good for social development. We think the energy revolution scenario can generate about 3.2 million jobs by 2050 in the global power supply sector alone.

Right now everybody is talking green – it’s become super fashionable. Many governments are talking about a green economy [but], if we are brutally honest, it’s business as usual. So in Rio+20 and in our work more generally, Greenpeace will strongly oppose any green washing and demand decisive action, which in some cases is going to be painful and complex. But the failure to make those changes now will be catastrophic, not only for the climate, not only for our children’s future, but for business, and will create social instability in a way that will be catastrophic for governments as well.

The scenario that you have just outlined requires not just buy in from governments but, if you are going to enact energy efficiency, then buy in from the public, especially in the developed world.

Let’s be honest about what’s happening with the challenge about public opinion. Activism comes up against – historically and presently – the most organised, influential, deep-pocketed sector of the economy in the form of the oil, coal and gas companies. In the US, for every member of congress [there are] at least three full-time lobbyists funded by the fossil fuel industry. For years, I have been saying that the US democracy is the best democracy money can buy. Now, when I look more closely at the most powerful interests, it’s not incorrect to say that the US democracy has become the best democracy fossil fuel money can buy.

The cards are stacked against us on one level, but things are actually shifting and I have a lot of faith in young people actually. Young people get it – they are concerned, they are beginning to organise around it in very inspirational ways. If you look at the number of women’s groups, trade unions, faith groups that ten years ago were standing up and calling for a green revolution, it was significantly smaller. Today I would argue that climate change is not solely an environmental issue. It’s an issue of peace, of development, of North-South balance. It cuts across everything.

Opinion seems to have been divided on the success of the COP17 climate summit in Durban, South Africa, last year. What were your impressions of the meeting and how well do you feel that the UNFCCC (UN Framework Convention on Climate Change) process works?

It’s funny when the place you grew up in becomes a conference rather than a city! [Laughs.] I would not call Durban a success at all. We need to point the finger at particular countries. We saw the US stopping several positive efforts to move to a binding agreement. Powerful governments – Canada, Australia, even China and India – cannot hide behind the United States and its willingness to delay urgent action. In Bali [COP13, 2007], on the last day of the last plenary, when everything was stuck, a delegation from Papua New Guinea said to the US, “If you don’t understand how urgent things are, OK, we failed to convince you, but please get out of the way and let the rest of us move forward.”

The fundamental problem is not the UNFCCC [but] the positions powerful countries come to the negotiations with. I’m not saying the UNFCCC is perfect, but I certainly don’t think that it is fair to blame it when it is governments that should carry the responsibility.

You said the US should get out of the way but can there actually be a meaningful resolution if America isn’t on board?

Obviously, it’s preferable to have the US. I think one of the best ways to get the US to come to the party is for the other countries to move ahead. If the US is isolated, they will see that they are going to compromise their economic future if they continue to hang on to dirty brown fossil fuel as a key driver of the economy. If they can see others moving in decisive directions, then economic imperatives, as much as environmental and climate concentrations, will shift the US into taking more action.

In June last year you defied a court injunction and boarded an oil rig 120 km off the west coast of Greenland. Why did you feel that action was merited? And why is it more important to stop fossil fuel exploration and extraction in the Arctic than in, say, Sub Saharan Africa?

One of the defining environmental challenges of our age is to fight against the insanity of a mindset that sees the melting of the Arctic Sea ice as a good thing. As the ice retreats, the oil companies, rather than seeing it as a warning sign that climate change is real, are trying to look for even more fossil fuels.

Why [is] the Arctic so important? A major oil spill in the Arctic would be catastrophic. Experts say it would be virtually impossible to clean up a spill due to the conditions. Let’s say there’s an oil spill in September and then the water freezes with the oil in it. The Deep Water Horizon spill in the Gulf of Mexico needed 6,000 vessels to try to clean it up, and in the end they only managed to clean about 17 or 18 percent of the oil. Even the US Coast Guard had made it clear [that] there is no way they could deploy that number of vessels to deal with a blow-up in the Arctic.

But does that mean that the struggle to stop dependency on oil, coal and natural gas is not being fought in other places? No. It’s not a question of saying that oil exploration in Sub-Saharan Africa is a good thing, of course not, but as an organisation we also have to think where we can add the greatest value.

Greenpeace is sometimes criticised for having an anti-science stance. What’s your response to this?

This is blatantly untrue. We strongly believe that science is crucial. We ourselves have invested in a science unit, which is based at the University of Exeter. We have laboratories there that provide scientific advice and analytical support to Greenpeace offices worldwide, over a range of disciplines from toxics to sustainable agriculture. In making the choices on climate, we’re completely 100,000 percent led by what the scientists say. What we should do in oceans, what we should do in forests and so on, is completely determined by the consensus in the scientific community. So I think that criticism is actually not based in reality.

Last year, Greenpeace celebrated its 40th birthday. Is the organisation settling comfortably into middle-aged conformity or is there perhaps a midlife crisis on the horizon? Maybe you are trying to prove that 40 is the new 20?

What’s wrong with being 40? I’m in my 40s [laughs]. Well, it’s not so much a question of being the new 20, but more a question of only being as old as our newest idea or our newest office. The organisation still remains committed to being a witness to injustice and follows some of the same methodologies that [have] worked well for us over the last four decades. But we are also reinventing ourselves and ensuring that we adapt to a fast-changing external environment. The process of adaptation can be painful, but on the other hand, rising up to a challenge can be a moment of creativity, innovation and excitement. I am trying to ensure that that’s the kind of spirit we’re creating here at Greenpeace.

You cut your teeth as an activist during the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. Do you see any similarities between the fight against apartheid and the battle for climate justice?

Growing up in Durban, there was a negative attitude towards the environmental movement because it was perceived as what white people did. People used to say, “Ah, environmentalists care more about animals and trees than they care about the majority of the people in our country.”

I don’t look at it as that I used to work combating poverty and now I’m working on environmental issues. I think an activist is an activist, and I’m an activist first and foremost. I remember the day Greenpeace became a possibility for me, I was in the midst of a hunger strike to push my government to change its position on Robert Mugabe. I got a call from Greenpeace on the 19th day of a 21-day hunger strike and I went, “Thanks, but this is bad timing.” That evening, my daughter called me and said, “Dad, if you don’t consider this I won’t even talk to you because this is about my future. Me and my friends talk about this all the time and Greenpeace doesn’t just talk, talk, talk, it takes action and that’s what we need right now!” She was 16 then.

So, when I look at the struggle to end poverty and the struggle to revert catastrophic climate change, they are two sides of the same coin. I think one of the big problems we’ve had is [that] we tend to put everything in compartments, and we need to change that. Unless we understand the intersectionality between the different challenges that humanity faces, and not set up development and the environment as being a contradiction, we don’t stand a chance to actually secure a peaceful and sustainable future for our children and grandchildren.

Interview by Elissa Jobson