The combined opposition parties’ power to outvote Guyana’s new government on crucial issues has created an unprecedented challenge to the politicians, who are now faced with a choice between finding a compromise and returning to the electorate for a new mandate.

Thanks to Guyana’s unique constitution, President Donald Ramotar was elected to office on 28 November 2011 as leader of the largest party, even though it holds only a minority of seats in the National Assembly. And as a consequence, the combined opposition has been flexing its muscles in questioning every aspect of government spending. Political observers predict that the president’s minority administration will be forced to hold fresh elections soon or else face the likelihood of the opposition-controlled National Assembly rejecting the budget and paralysing all government activity.

Guyana’s complex constitution, revised in 1980, provides for an electoral system of proportional representation under which the country is divided into ten regions returning 25 members of the National Assembly with another 40 seats being allocated nationally on the proportion of votes cast for each party. To control the assembly – which makes the laws of the country and initiates its money bills, including the budget – a party must secure more than 50 percent of the ballots. At the same time, according to the constitution, the president, in whom executive authority lies, only requires a plurality of the votes to be elected.

Since his People’s Progressive Party/ Civic (PPP/C) received the highest number of votes cast for a single party (48.7 percent), Ramotar was elected president even though the PPP/C, as a party, does not control the National Assembly. The PPP/C holds 32 seats in the 65-seat assembly, while A Partnership for National Unity (APNU) has 26 and the Alliance for Change (AFC) seven, giving the opposition parties a one-seat majority if they act together.

Even if the two opposition parties now tried to form an alliance – something they failed to do before the elections – they cannot form a government. The constitution requires the president to appoint the prime minister and ministers from “among the elected members of the National Assembly” and Ramotar chose to form a minority government made up exclusively of members of his PPP/C. Ramotar, who was general secretary of his party, succeeded Bharat Jagdeo, who had served as president for 12 years, but who was prohibited, under an amendment to the constitution, from seeking another term.

Ever since 1953, when a row between the original PPP’s two main leaders, Cheddi Jagan and Forbes Burnham, caused a split, Guyana’s general elections have been problematic. The split resulted in Jagan continuing to lead the PPP and Burnham forming the People’s National Congress (PNC). Racial considerations have since dominated elections, as the PPP became an East Indian-based party and the PNC derived its following from the African community.

In what is now well-documented history, the British government imposed an electoral system of proportional representation on British Guiana (as Guyana then was) in 1963 at the insistence of US President John F. Kennedy, who feared that, under Cheddi Jagan, Guyana would become another Cuba on America’s doorstep.

The first elections under the system of proportional representation in 1964 resulted in the ousting of the PPP and the election of the PNC in a pre-election coalition with a third party, the United Force. Every subsequent general election was reportedly rigged by Burnham and the PNC until 1992, when former US President Jimmy Carter and the Carter Center supervised the process. It was under Burnham, who died in 1987, that the constitution was changed to allow for the president to be elected on a plurality of the vote even if his party failed to secure an overall majority in the National Assembly.

Although Jagan, who brought the PPP/C to office in the 1992 elections, had undertaken to change the constitution and remove the anomaly, this was never done by him or his successors in office (first his wife, Janet, and then Bharat Jagdeo).

After 1992, the PNC failed to attract wide support, and this was particularly obvious after the death of Burnham’s successor, Desmond Hoyte. By the run-up to the general elections of 2011, it was clear that the PNC, under its leader Robert Corbin, was in no position to win and so it joined the Working People’s Alliance and two smaller parties to form APNU, under the leadership of David Granger, a retired army officer. Each participating party maintained its own identity. The alliance was for the sole purpose of contesting the election and toppling the PPP/C.

The AFC, which has emerged as a third force over the last ten years, refused to join the alliance. Its main platform was an end to racial politics and an appeal to Guyanese as one nation. The AFC said it wanted no contamination by the politics of either the PPP/C or the PNC.

However, since the November elections, the AFC has joined the APNU in giving stiff opposition to the minority PPP/C government. On 10 February, using their combined majority, they demanded explanations and documentation to justify expenditures that the government has already made but brought to the assembly for approval as ‘supplementary’ expenditure to last year’s budget. In a spirited response, the minister of finance, Ashni Singh, said: “What manifested itself is a willingness to use their vote on projects that are unchallengeable solely for the purposes of saying ‘we have the majority’.”

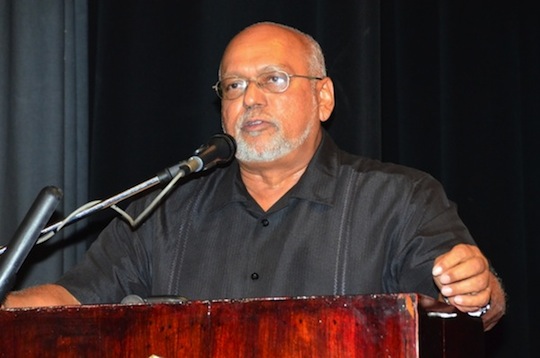

President Ramotar declared: “As willing as my government is to exercise patience, forbearance and reasonableness in the interest of all of our people, my administration will not be held ransom to intractable postures.”

In the absence of a bipartisan approach to the content of the budget, it will undoubtedly be extremely contentious and might not be accepted by the combined opposition. The parties’ actions seem most likely to be decided by gambling on whether or not a fresh general election will result in one party winning an overall majority.

The shame of it is that a government of national unity is not being offered as an option. Yet that may very well be the only course that would give Guyana the political stability to take advantage of the country’s significant economic bounty and the impressive strides it has made over the last six years.