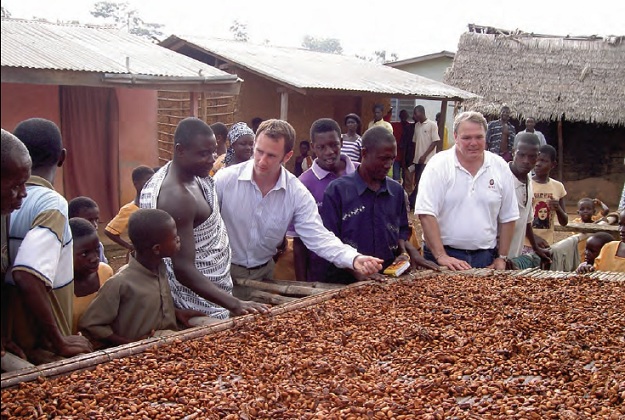

The world’s second largest producer of cocoa – and rich in natural resources, including gold and oil – Ghana was destined to lead Africa’s fastest growing ‘lion’ economies over the next ten years. But falling gold prices and falling tax receipts have set back economic growth

For the past 15 years, the management of Ghana’s economy has been held up – by multilateral organisations such as the World Bank, among others – as the exemplary model for other developing countries to follow. The country has enjoyed political stability, good macroeconomic management, a steady annual growth in the five per cent range and a diversified economy based on gold mining, manufacturing and cocoa – Ghana is the world’s second largest producer. It is now also an important oil producer and has the potential to become the third largest oil producer in Africa.

Indeed, by 2010, when the country’s first oil began to flow from the Jubilee field and the price of gold nudged the US$2,000 per ounce mark, a recalculation of the country’s GDP, based on more relevant data, raised GDP by 60 per cent. Growth was estimated at around 14 per cent and Ghana entered the ranks of middle-income countries.

It seemed that Ghana was destined to lead the pack of the ‘African lions’ – a dozen or so fast growing countries – over the next decade at least. But during the last few months, the country’s serene progress towards its medium term annual growth target of eight per cent has suffered several setbacks and the ‘black swan’, in the form of a catastrophic fall in the international price of gold, has made its dreaded appearance.

However, even before gold lost 25 per cent of its value between April and June – the biggest quarterly drop since 1968 – it was clear that all was not well with the Ghanaian economy. Expenditure had severely outrun revenue and left a 12 per cent deficit black hole that is threatening to undermine many of the gains made leading to 2012. The Minister for Finance, Seth Terkper, has blamed the deficit on shortfalls in corporate income taxes and grants from development partners, higher interest costs, fuel and utility subsidies, and higher spending on goods and services.

While Ghana’s upgrading to middle income status confirms the success of its economic policies and makes it much more attractive to foreign investors, it also means that the country loses a number of its sources of donor support. “As we consolidate our middle income status and these facilities become less available to us, we should be in a position to borrow effectively from the capital markets,” says Terkper. In June Ghana issued a $1 billion Eurobond which Terkper says will help reduce the deficit to six per cent of GDP by 2015. But this will not be enough, according to the IMF.

“The government’s deficit target of six per cent of GDP by 2015 will keep public debt high and buffers low so the mission recommended an additional fiscal adjustment of three per cent of GDP by 2015,” says Chistina Daseking, leader of an IMF mission to Ghana. This will be a tall order for the government, especially as its tax assessment and collection regime is inefficient and many still avoid paying taxes, while the large informal sector remains outside the system. The Finance Minister has promised reforms of the system and says he will widen the net to plug loopholes.

In the meantime, efforts to claw back the deficit by raising the taxes of corporations that do pay their taxes, such as those in the mining industry, could rebound badly, especially when the outlook for gold is becoming dimmer by the day. Corporate mining tax was increased from 25 per cent to 35 per cent, capital allowance standardised to 20 per cent and a bill to introduce a 10 per cent windfall tax is on its way.

The mining sector is already the largest taxpayer in the country, contributing 27 per cent of total direct taxes to the Ghana Revenue Authority’s domestic collections. It also contributed 37 per cent of the total corporate tax collected in 2012. Mining companies complain that the cost of production in Ghana is already steep and ate up 70 per cent of the $4.6 billion in revenue generated from gold mining in 2011. The extra burden could be the last straw. “Excessive taxation on mining could be disruptive and kill the goose that lays the golden eggs,” director of analysis, research and finance at the Chamber of Mines, Sulemanu Koney, points out.

In June, Nick Holland, Gold Fields CEO, said: “The industry is not sustainable at $1,230 an ounce, which is where the gold price is at the moment. We’re going to need at least $1,500 an ounce to sustain this industry in any reasonable form.”

Some 40 per cent of Gold Field’s output comes from Ghana. Other major miners include AngloGold Ashanti and Newmont. In 2011, Ghana produced 91 tonnes of gold, contributing roughly 12 per cent to the country’s GDP. Despite the anticipation drummed up by oil, mining and cocoa will remain the main pillars of the Ghanaian economy for at least the rest of this decade and both require handling with velvet gloves. Several gold mines around the world and in South Africa have already been mothballed until the gold price recovers to a level when mining is again sustainable.

Despite these setbacks, however, the Ghanaian economy has been built on solid foundations and whatever it may lose on the gold swings in the short run, it can gain on the oil roundabouts when production rises from its current 125,000 barrels per day (b/pd) to 250,000 b/pd when phase two of the Jubilee project is completed and several more fields begin production. If all the commercial discoveries made so far come on stream, Ghana could well become the third largest oil producer in Africa after Nigeria and Angola.

In addition, the Ghana Gas Company, set up in 2011 to avoid the wasteful flaring of natural gas that characterised the early years of the Nigerian oil industry, was expected to start production in July, but delays in the release of funds from the Chinese government have held up the project.

Gas will be supplied to the Tema and Takoradi power plants, while the 400 MW Bui hydro scheme, which is being developed by Sino Hydro, will add to the energy mix and, hopefully, not only end the country’s chronic shortage of power but also leave a surplus for export.

While Ghana has made enormous strides, its economic planners now have to show a nimbleness of foot to cope with unexpected hurdles, fiscal discipline to put a cap on spending while raising domestic tax revenue and imaginative leaps to create more job opportunities and spread the fruits of growth far more equitably than at present. The middle distance race has more or less been won – now comes the long haul of the marathon. Does Ghana have the staying power?