The Syrian conflict shows no signs of abating and half of the country’s population is now displaced, creating the largest volume of refugees since World War II

While the world’s politicians search for a workable solution to the Syrian refugee crisis, millions of asylum seekers are languishing in makeshift camps, or sleeping rough on the streets, waiting for hostilities to end. More than half of Syria’s pre-war population of 23 million is currently displaced and, while some have found shelter in other parts of Syria, many more have crossed borders into neighbouring countries or are en route to Europe in search of a fresh start.

While the world’s politicians search for a workable solution to the Syrian refugee crisis, millions of asylum seekers are languishing in makeshift camps, or sleeping rough on the streets, waiting for hostilities to end. More than half of Syria’s pre-war population of 23 million is currently displaced and, while some have found shelter in other parts of Syria, many more have crossed borders into neighbouring countries or are en route to Europe in search of a fresh start.

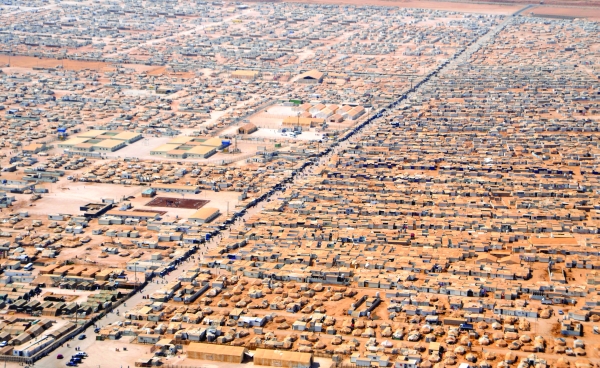

The majority of Syrian refugees have taken shelter in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan – by September Jordan had 629,245 refugees, Turkey 1,938,999 and Lebanon 1,172,753. This means that one in five people living in Lebanon are refugees, while Jordan’s Za’atari camp is now the country’s third largest city.

Those who flee are escaping not just the fighting in their towns and cities, but also human rights abuses and a lack of basic necessities, including food and medical care. Most are also leaving without much paperwork. Many Syrians do not have passports and for those who did, the deteriorating political situation since the start of the civil war has made it difficult to renew passports or to acquire visas to leave the country through official channels. Hence why so many Syrians, along with asylum seekers from other countries facing difficult conditions, have been risking their lives by getting into boats heading from Turkey to Greece, Italy or Malta, in order to apply for asylum in Europe. It is this swell of people travelling through Europe to try to get to the West that has brought the situation to international headlines.

“Even Syrians call the boats to Europe ‘death’ boats,” says Rory O’Keeffe, journalist and author of The Toss of a Coin: Voices of a Modern Crisis. “They know that the boats sink and they know that if theirs sinks they’re likely to drown. But they’re that desperate to get out so they can start again that they will give it a go to give themselves an opportunity.”

Although Jordan, Lebanon or Turkey may seem like a more obvious destination for a refugee from Syria than Europe, none of these countries allow refugees to work. In Jordan there are camps run by the UN and the Jordanian government, but in Lebanon there are no official camps, other than the makeshift ones that refugees have set up for themselves and the situation is similar in Turkey.

“Lebanon has pulled out all the stops, but if any country can say that it’s been genuinely overrun, it’s Lebanon,” says O’Keeffe. “The population of Lebanon has increased by 25 per cent in the last four years. And its infrastructure has been stretched to breaking point. What Lebanon expected to happen, but what hasn’t happened, is that richer countries would step in and say, ‘Right you’ve taken these people in, we will take some of them and they can live here until they can go home.’”

Many refugees staying in other Middle Eastern countries find work in the black economy where they can, and end up living in derelict buildings or homemade shelters. For those that go to the official UN camps, there are other challenges. Jordan is struggling to provide enough water for all the refugees – it is the fourth water-poorest country in the world. And, while education is provided in the camps for children of school age, provision is patchy and not all children have been able to take advantage of it. There are also problems with crime, particularly rape. But, on the plus side, healthcare is available and, at Za’atari, small businesses have been springing up to provide additional services to other residents, including the sale of fruit and vegetables and even wedding dresses.

“Nobody really wants to sit in a tent for six months waiting for their life to start again. You just have the feeling in a refugee camp that everybody’s life is on pause. They’re just sitting and waiting to be able to start their lives again. It’s not that they’re desperate to go somewhere else, it’s just that they know they can’t go home and they want to be able to start working again and start their lives again,” says O’Keeffe who has worked for NGOs that support refugees in the Middle East.

“One of the problems at the Za’atari refugee camp is that the numbers fluctuate massively. Every time Syrians hear that fighting has moved away from their area, they go back because they want to just get on with their lives. And then the fighting comes back and they just get swept back to Za’atari, which makes it very difficult to run the camp. It makes it hard to provide education; it makes it hard to provide enough food and water for everyone.”

Many people have wondered why other nearby Arab countries, like Saudi Arabia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates haven’t done more to take in refugees. “I think every country could do more, other than Lebanon, Jordan, Greece, Iraq and Turkey,” says O’Keeffe. “In the Gulf, only Iraq has refugees – about 250,000 of them, despite having a civil war itself. Yemen is also caught up in a civil war.

“One thing to remember is that Saudi has traditionally been an enemy of Syria and has opposed Assad at every turn – particularly because Assad happens to belong to a different branch of Islam to the royal family. Assad is relatively secular and opposes the monarchy. And, obviously, Saudi is a religious state run on entirely monarchical lines. So Saudi Arabia may not be particularly inclined to take Syrian refugees in a crisis. From a Syrian perspective, the chances are Saudi is not a state that you would aspire to live in. I know there’s the argument that if you’re desperate you’ll do anything, but the idea of living in a monarchy run on religious grounds, particularly for women who are used to having more rights and freedom, isn’t something you’d want if there is an alternative.”

While the EU discusses how to cope with the influx of asylum seekers, some European countries are notably doing more than others to try to accommodate their fair share of refugees. O’Keeffe admits to being disappointed by the response of his own country, Britain, which has said it will take in 20,000 Syrian refugees over the next five years. Germany started out with the best of intentions, when it said it would open its borders to refugees, but had to backtrack from that when the sheer numbers of arrivals became too much. It is expecting to take in in the region of 800,000 people. France has agreed to take 24,000. Most Eastern European countries have been reluctant to commit to accepting asylum seekers, beyond letting them pass through on the way to Western Europe.

Mercy Corps, a charity that provides emergency relief in disaster and conflicts, believes that ordinary people can help persuade their governments to do more. Javier Alvarez, senior team leader for Mercy Corps’ Strategic Response and Global Emergencies team, says: “If there is anything positive from the current situation, it’s that in Germany and the rest of Europe people are asking their government to be accountable to these refugees. That is a sign that people are very sensitive to this issue. People are starting to really care about these things. In Greece we saw volunteers from Hungary, New Zealand, Australia coming to help refugees. There is international solidarity and we should all be channelling that good into pressuring governments to take action. I think what we’re seeing there is a very positive sign that we can do something.”

If there is one conclusion to be drawn from the Syrian refugee crisis it is that international, and domestic, protocols for granting asylum to refugees were never intended to cope with millions of people seeking refugee status at the time. The requirement of applying for asylum in the first safe country reached is not workable when it puts an unacceptable burden onto those nations bordering a country at war – and others in the region that have a long coastline – and absolves those slightly further away of a duty to help. The 1951 Refugee Convention may need to be revisited as a result of Syria’s civil war.