Concern about the environmental impacts of the oil and mining industries has spread to the wider financial, economic and even political effects of the lucrative deals that govern valuable extractive industries in poor countries, setting in motion a genuine transparency revolution.

A transparency revolution in the oil, gas and mining industries is under way. After a decade of campaigning and progress that was slow at fi rst, this quiet movement for change may be reaching a global tipping point. New information is coming into the public domain – and will emerge in the next few years – which may profoundly change the relationship between citizens, states and companies in resource-rich countries and bring more accountability to the way billions of dollars of natural resources are managed.

In the more than 50 countries that are classifi ed as ‘resource-rich’ by the IMF, there are in excess of 1.5 billion people living on less than $2 a day. Up until the late 1990s, few had really thought to question this tragic irony and so the grand game played on. Oil and mining companies scoured the globe for resources and found host governments happily willing to keep the deals and payments secret from citizens, parliaments and journalists. International lenders like the World Bank and export credit agencies from Western industrialised countries lined up to provide catalytic fi nancing for these extractive industries projects.

By the late 1990s and early 2000s, international NGOs started looking into these issues and they didn’t like what they saw. Groundbreaking research reports by groups such as Oxfam America, Human Rights Watch, Global Witness, Catholic Relief Services and others begin to examine how the so-called ‘resource curse’ or ‘paradox of plenty’ was playing out in poor but resource-rich countries like Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo, Ghana, Nigeria, Peru and elsewhere. Corruption, conflict, poverty and environmental degradation were the norm, rather than the exception.

A major problem identified was the secret payments being made by extractive companies to host governments and the secret contracts that governed the deals. The ‘Publish What You Pay’ coalition was set up by a number of leading international NGOs. The global coalition now operates in over 30 countries with more than 600 members, campaigning to put new rules in place to compel disclosure of payments to governments, contracts governing resource extraction and government budgets using these revenues. Without information, local citizens, civil society groups, parliamentarians and journalists won’t be able to ask questions or start a democratic debate on how – and whether – these resources should be developed.

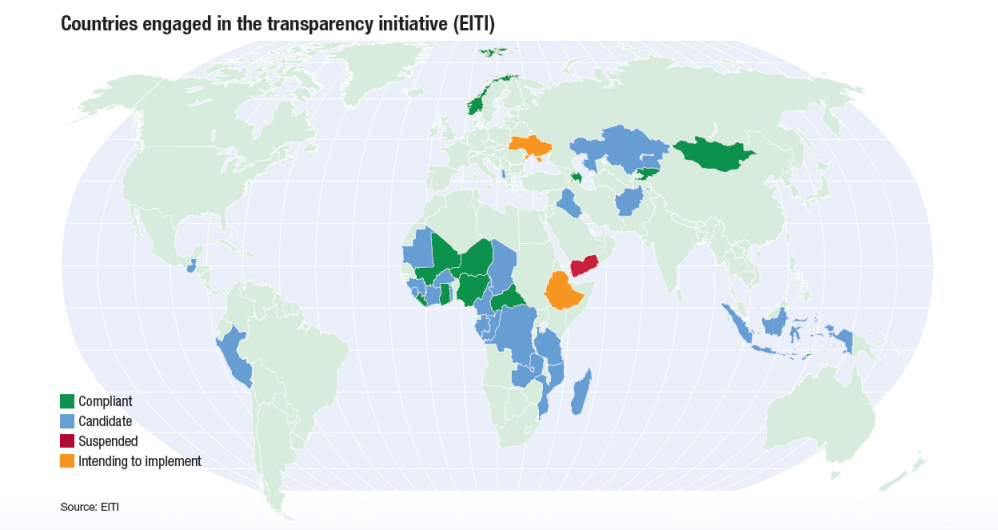

Everyone may say that they favour transparency, but it has been a long, hard slog to achieve it. While many corporate and government interests have been intent on maintaining the secrecy status quo, their resistance is now crumbling at last. The first crack came with the establishment of the international Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI) in 2006. For the first time, companies, governments, civil society groups, investors and donors agreed on a formal structure to increase the transparency of payments.

In fits and starts, EITI has made some progress, setting a minimum standard for payment disclosure that all sides could agree on. EITI is voluntary in the sense that countries have to exhibit the political will to join and then fully implement the programme. Ten countries are now considered ‘compliant’ under the rules (see map above). Of course, the countries where the problems are most severe are least likely to join or implement the initiative.

A further notable advance came in 2007 when the World Bank’s private-sector lending arm – the International Finance Corporation (IFC) – began to require payment disclosure for all the oil, gas and mining projects it finances. Previously, IFC staff had claimed this idea was a non-starter and that private sector clients would go elsewhere if such disclosure was required. In fact, IFC business has not fallen off and the private sector continues to supply significant funding for global mining projects. The IFC has even changed its policies to require disclosure of the underlying contracts themselves as a condition of financing – the first international lender to make such a bold move.

But perhaps the ‘shot heard round the world’ was the passage in 2010 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform Act in the USA. Buried in the legislation is a groundbreaking provision requiring all oil, gas and mining companies reporting to the US stock exchange regulator, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), to disclose payments on a country-by-country and project-by-project basis, broken down by payment types (royalties, taxes, etc).

This provision will set a much higher bar than EITI, will cover US and non-US companies – not only Exxon, Chevron, Shell, BP, Total, Petrobras and PetroChina but many others – and builds on stand-alone bipartisan legislation introduced by senators Cardin and Lugar in 2009.

The industry response has been to try to water down implementation. The oil companies have claimed that these disclosures could harm them competitively, even though several oil and mining companies, such as Norway’s Statoil and Canada’s Talisman Energy, already disclose this information in every country of operation. If it truly hurt their bottom line, these firms would not be doing it; the law does not require the disclosure of sensitive information regarding commercial terms, proprietary technology, business models or contracts.

Companies have argued that they should not be expected to disclose if local laws prohibit disclosure but they have been unable to produce evidence of such laws. If such an exemption were to be granted, this would simply be a signal for companies and governments to collude to develop new legislation to continue secret arrangements.

In support of Dodd-Frank, investors with assets valued at more than $1.2 trillion have told the SEC that the provision will provide important information for investors to assess risk. The US Agency for International Development has said that strong implementation will support the international development objectives of the US government. The US Department of the Interior has agreed that implementation of the law “could be very useful” as it seeks “to ensure that energy companies are reporting correctly and paying every dollar due to the American tax payer”. The SEC now plans to issue final implementing regulations before the end of 2011.

With the passage of Dodd-Frank, European leaders are now preparing to follow the US lead. French President Nicolas Sarkozy, UK Prime Minister David Cameron and other European officials have endorsed an EU-wide regulation along the same lines. In June, the 2011 G8 declaration endorsed mandatory disclosure laws and José Manuel Barroso, president of the European Commission, has committed to advancing legislation in Europe, with a proposal due to be tabled before the end of the year.

Progress in global financial centres has been matched by progressive laws in resource-rich countries themselves. Countries such as Ghana, Liberia and Nigeria have all recently passed legislation requiring the disclosure of the extractive industries payments. Ghana’s 2011 Petroleum Revenue Management Act, coupled with country’s oil revenue management efforts. In addition, Ghana’s petroleum agreements are available online at its energy ministry website for public inspection.

At last, the international development agenda addresses the problems of resource-rich countries and of the largely untapped potential of extractive industry revenues being used to reduce poverty. New ‘hard’ and ‘soft’ laws are in place and the momentum has tilted in favour of transparency as the norm, rather than the exception. As official aid dollars dry up, it will be more important than ever to make the most of government revenues from all sources to ensure progress on health, education, agricultural investment and other vital needs for the poor. Groups around the world are using newly disclosed information to hold their own governments accountable for spending extractive industry revenues.

But the transparency agenda is unfinished. While transparency is increasing in many parts of the world, citizens and activists who use this information and ask uncomfortable questions are often under threat. Governments are enacting new laws to restrict freedom of association and the operation of local NGOs. And more information needs to be disclosed to be able to ‘follow the money’ from its source.

Government processes for licensing new oil or mineral deposits are often opaque. Shadowy companies, generally involving local elites, gain interests in new fields and their ‘beneficial ownership’ is never disclosed. More lenders and countries need to require by policy and law the disclosure of the underlying agreements for these projects. Finally, the way that governments market their share of oil production also remains shrouded in secrecy – these agreements must be made known.

The transparency revolution may be incomplete but it is clearly well under way and there can be no turning back to the days of secrecy and silence.