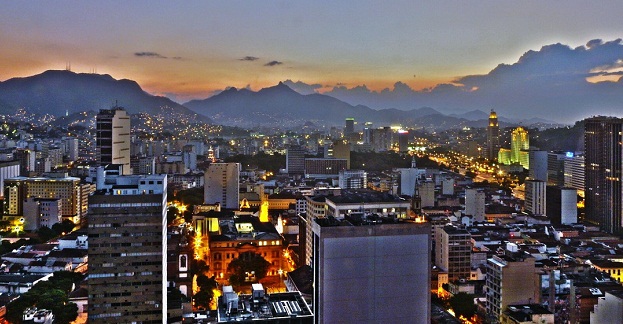

When heads of state gather in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, in June for the UN Conference on Sustainable Development – dubbed Rio+20 to recall the first Earth Summit held in the city 20 years ago – there will be plenty of evidence of the ongoing shift in balance in the world economy. The international development agenda is passing from the rich countries to rapidly emerging nations like Brazil and China as the West still grapples with its economic crisis.

With the UN system requiring consensus, what has too often been missing from environmental negotiations is the political will to achieve change. At least the passion among ordinary people to better protect the planet is still growing, and so the final message arising from Rio+20 is likely to be: less talk and more action on genuinely sustainable development, writes The Guardian‘s Environment Editor John Vidal.

Having just overtaken Britain as the world’s sixth largest economy and on course to be bigger than Germany in a decade, Brazil, a country of 200 million people, is determined to brand itself as the world leader in sustainable development. So what could possibly go wrong with Rio+20, the largest conference on environment and development in 20 years? The answer is plenty. The backdrop of a Western economic crisis has led to a sharp decline in public trust in government, protests around the world are questioning the whole market economy and, because the UN works by consensus, one rogue country or group could pull the whole summit down.

Compared to the high ideals of the first Rio Earth Summit, the Rio+20 agenda looks tame. Countries will be only asked to sign up to ‘a roadmap’ to the ‘green economy’, and to eight new sustainable development goals (SDGs) to run parallel to the millennium development goals (MDGs). On the table, too, is a long overdue agreement to protect oceans, and the UN wants to see its small environment programme grow into a fully fledged agency on a par with the World Health Organization.

But no country will be asked to sign any document that would legally commit it to meeting any particular targets or timetables – as ever in UN negotiations, nothing is agreed until everything is. But fundamental differences and red lines are already emerging that suggest Brazil will be hard-pressed to prevent disaster at the worst, or a watered down set of meaningless agreements at best.

Problem 1 is the overarching commitment to work towards the ‘green economy’ – something considered potentially threatening to many countries. Everyone wants to see action rather than words, but the USA is likely to balk at what it fears will be targets, timetables and restrictions. Equally, China won’t stand for being told what development path it should take. Most countries will agree to national action plans to adopt green technologies and accept new national accounting methods to assess resource use. But will countries like the projected phasing out of subsidies for fossil fuels? The danger is that the green economy gets mixed up with trade and climate change talks and is ditched as too vague or complicated.

Problem 2 will be the SDGs. All countries will be asked to set themselves voluntary targets on food safety, water, energy, oceans, eradication of poverty and sustainable patterns for production and consumption.

Everyone likes the voluntary bit, but powerful national interest groups are already fighting to avoid any moves that could help rivals.

Problem 3 will be the institutional changes that the UN wants to see. Countries recognise the Nairobi-based UN Environment Programme is weak, having a small budget and only 60 or so members. But the USA, China, India, Russia and others are, so far, sceptical about changing its status to a formal agency, which would give it powers to set international law.

Brazil is confident there will be agreements in all major areas, but the lasting legacy of the conference is likely to be the effective handover of the international development agenda from the rich countries to the rapidly emerging nations like Brazil, China, India, Indonesia and Mexico. Together, they make up 80 percent of the world population and with the West staggering from one economic crisis to the next, they now effectively control the world’s resources.

Equally, the new ideas at Rio will come from the South, rather than the North. In the wake of the 1992 Rio conference, the world saw the emergence of vast new grassroots, farming and indigenous peoples movements in developing countries as well as the empowerment of local authorities and growing awareness of the problems by cities, businesses and NGOs. Now, 20 years on, the world has 1.5 billion more people and has shifted from being rural to predominantly urban. The concerns of cities, the landless and the hungry are more likely to be reflected.

Rio will see new ideas put on the global map with small countries linking with NGOs to propose ways out of the impasse. Western based international NGOs will be present but above all Rio will be a laboratory of ideas for the dynamic social movements and indigenous peoples of Latin America, Africa and India.

The world leaders may grab the headlines, but some of the smallest countries could steal the show with ideas for change. Bolivia will press for laws granting nature equal rights to humans, while Ecuador will favour ways to reward countries for not extracting fossil fuels. But the most radical of all may come from the tiny Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan, which hopes to garner support for a global summit it wants to host on happiness and well-being.

“The world is at a crossroads,” says Daw Penjo, Bhutan’s acting foreign minister. “We wish to invite and host the nations of the world in 2014 at a historic meeting that will officially replace the 1944 Bretton Woods consensus [that set up the present International Monetary Fund]… with a new historic global accord on a sustainability-based economic system.

“If we are to gather in Rio in another 20 years to celebrate our triumph in turning round our present suicidal course, then we must begin immediately to take the value of natural capital ecosystem services and social well-being fully into account and begin to chart a sane path into the future.”

And who could possibly disagree with that?