Tanzania’s trademark art style has become representative of African art the world over – but is it staunching the market for new forms of African art?

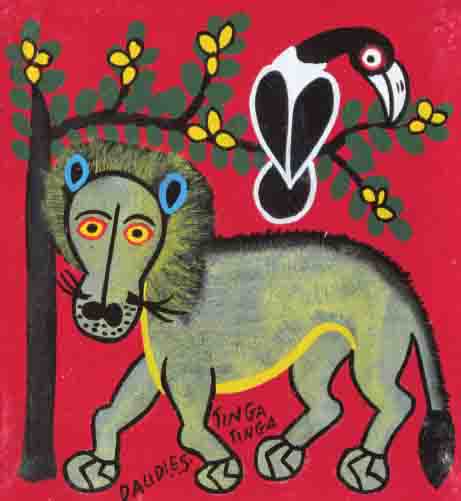

Picture: Daudi Tingatinga. With special thanks to Daniel Augusta and TANART for supplying the image reproduced here: www.TingaTingaStudio.com

Tinga Tinga’s colourful, caricatural style is instantly recognisable. Often heralded as simplistic and naïve – think kids’ cartoon Tinga Tinga Tales – it uses broad lines and bright colours to portray its subjects in an expressive and often humorous way. More than 40 years since its inception by Edward Saidi Tingatinga, the style is more popular than ever – and its appeal is growing.

Daniel Augusta, managing director of TANART, the Tanzania Art and Licensing Agency, tries to explain its popularity through an analogy with Darwinian theory. “In biology there is interaction between species (paintings) and environment, including the predators (customers). Now, if the environment changes (the taste of customers), the species changes to the new conditions (the broad variation of paintings). The survival of fittest is the concept.”

While in other countries, art has been nurtured by wealthy patrons, Tanzania’s trademark style draws its support from the tourism sector. As a result, artists have had to cater to their visitors, reproducing designs and subjects that have proven popular in the past in order to secure a living.

“It is the most popular painting which sells and thus provides means for the artist to further his art endeavour. And this painting is reproduced with small variations. What is important to understand is this: the artists cater for the taste of customers,” says Augusta. “And it is mutual interaction. Both the buyer and seller (customer and the artist) must come to an agreement which does not step over their cultural comfort zones.

“Some refer to it as tourist art, but many of the ‘tourists’ are curators – art dealers, museum employees, etc. So it could be called ‘curator art’,” says Augusta. “Suddenly it sounds much better!”

Tinga Tinga paintings are traditionally built up using layers upon layers of brightly coloured bicycle paint on Masonite – a type of wooden board – creating vibrant, colour-saturated pictures. These days, many artists use faster-drying enamel paint on small, tourist-friendly canvases in order to support the ‘airport art’ culture and promote saleability. Similarly, the subjects of such Tinga Tinga pictures tend to be stereotypically African, representing the ‘big five’ – lion, elephant, leopard, buffalo, rhinoceros – as well as wild fauna, people and villages. What started off as the artistic expression of one man has evolved into a legacy that has, on one hand, established a popular tourist trade that responds to market demand and, on the other, inspired hundreds of artists – there are currently around 700 practising Tinga Tinga artists in Tanzania – to develop their own take on the style.

But it is not an easy tradition to break from. Tinga Tinga has become an African trademark – it is the keepsake that every visitor to the continent hopes to bring home – and that has made it difficult for practitioners of other styles to get noticed.

“I would say that Tinga Tinga poses quite a big competitive threat. It is difficult to compete with because of price. Tinga Tinga paintings are cheaper than any other visual art in Tanzania,” says Augusta. “And Tinga Tinga is accepted as the genuine art of Tanzania too, so the artists may find it difficult to draw attention to their own creations.”

Whether choosing the route of mass-producing popular designs or testing the waters with more innovative work, Daniel Augusta explains that painters share a common goal.

“I think that the primary aim of Tinga Tinga painters is to sell their paintings,” he says. “There is no doubt about it.”

An aesthetic art, Tinga Tinga aims to represent the world in a striking way, rather than to mine it for meaning. There are, of course, some notable exceptions. For example, Mohammed Charinda’s paintings investigate serious issues, from the old slave trade to recent albino killings. But he pays a high price.

“His paintings are not selling as well as the mass-produced or the aesthetic ones. Still, the commercial aspect is Mr Charinda’s primary aim,” says Augusta. “He hopes to sell, as any other Tinga Tinga painter does.”

But there is another side to Tinga Tinga. It is not, as it is often called, entirely an ‘airport art’, reproducing the same designs over and over again in the style of a popularity production line. Tinga Tinga artists are many and diverse, although most must produce ‘popular’ art for sale first and foremost, and only then focus on more personal projects. Others must maintain a ‘day job’ to support their creative pursuits – after all, the stereotype of the impoverished artist is not particular to the West. And the outcomes of these artists’ work vary greatly, but still incorporate the unifying factors of Tinga Tinga – vibrancy of colour, vivid lines, and a certain something that is wholly and authentically African.

Daudi Tingatinga, the only son of Edward Saidi Tingatinga, the style’s namesake, has carried on his father’s legacy. Daudi’s paintings reflect the essence of the Tinga Tinga tradition in their simplicity – splayed poses and blocks of colour – and are particularly reminiscent of his father’s work.

Noel Kapanda’s work, on the other hand, is far more intricate. Usually depicting more than a single subject, Kapanda’s paintings show detail in their bird wings, tree leaves and leopard spots, using thinner, fluid curves and delving into the realm of gradients as well as using blocks of unbroken colour. “Kapanda,” states his Inside African Art profile, “is maybe the least-known Tinga Tinga painter in Dar es Salaam, but he should be the best known.”

Ally Wasia and David Mzuguno both paint flora, but their styles differ magnificently. Mzuguno’s lines are more heavy handed and partition each element of his work into small and vivid segments. Meanwhile, Wasia’s lines are delicate, relying upon the colours of the paintings for their punch.

The Tinga Tinga aesthetic is said to derive from the African tradition of decorating hut walls with drawings of animals and people using natural pigments – a tradition observed particularly in south Tanzania. Developed in the Oyster Bay area of Dar es Salaam in the late 20th century, Tinga Tinga spread to become one of the most widely recognised art styles, not only in Tanzania but also Kenya and surrounding countries. The style is named after its founder, Edward Saidi Tingatinga, who popularised it beyond the continent by selling his paintings to expatriates – but he only got to focus on his art for a handful of years.

Having had no formal art training, Tingatinga painted out of passion in his spare hours, while working where he could during the day to support his wife and two children. In 1961 Tanzania’s independence swept in a tide of artists, mostly from Zaire, who peddled inexpensive paintings along Dar es Salaam’s main streets. Tingatinga, then between short bursts of employment, saw his neglected passion for the art rekindle. Borrowing household paint and a crude brush from a friend, he conducted his first picture on a makeshift canvas of rough ceiling board and went on to display it outside the Morogoro Stores in the centre of the city.

The painting brought him ten shillings and the promise of a new career. From then on, Tingatinga poured as much time as he could into his calling, while maintaining a nursing job at Muhimbili Hospital. In 1971 Tanzania’s National Arts Council displayed his work at two major exhibitions, resulting in a contract that supplied him with materials and took over the sale of his work.

But Tingatinga’s artistic career would last only a few short years. In 1972, at the age of 40, Tingatinga was shot and killed by a police officer who mistook him for a fugitive.

He left behind six students – Simon Mpata, January Linda, Adeus Matambwe, Kasper Henric Tedo, Abdallah Ajaba and Omari Amonde – who went on to form the Tinga Tinga Partnership. Under the umbrella of the Tinga Tinga Partnership the work of the artists expanded and in 1990 it was time to form a bigger organisation – the Tinga Tinga Arts Co-operative Society. Today the society has more than 50 active members, most of them related in some way to Tingatinga, with each member contributing 15 per cent of their sales to the co-operative to cover basic expenses.

The artists of the co-operative, based at the Morogoro Stores of Dar es Salaam, are also helping Tinga Tinga reach a new generation through their work with Kenya-based Tiger Aspect Productions. Tinga Tinga Tales is a children’s show that incorporates the art style with African creation stories, such as ‘Why Elephant Has a Trunk’ and ‘Why Vulture is Bald’, and has seen an excellent reception worldwide by young and old alike.

It is difficult to get to the root of Tinga Tinga’s popularity – perhaps because its appeal has to be felt rather than written down on paper. There is just something intrinsically likeable about the style’s bold contours, its unabashed colours and simplicity – something native to the sun and sound of Africa.

“I love Tinga Tinga because of its colours, naïve genre and close affinity to traditional African culture. It was not influenced much by the Western school of art,” says Augusta. “But Tinga Tinga is also a lifestyle for me. The art is much more than just paintings. The art is the people behind it, experiences, trips, visits and much more.”

He laughs: “Probably if Tinga Tinga was situated in UK, I wouldn’t be interested. It would be too rainy for me.”